The brainstem contains many neurones that do not belong to well defined groups such as the cranial nerve nuclei or the olivary nuclei, or fibre tracts such as the pyramidal tract, the medial lemniscus or the medial longitudinal bundle. The reticular substance of the brainstem, the tissue between the distinct specific nuclei or tracts, appears to consist of a hotchpotch of nerve cells without obvious similarities, and axons that pass in many directions, intersecting with each other, rather than travelling together in the form of a tract.

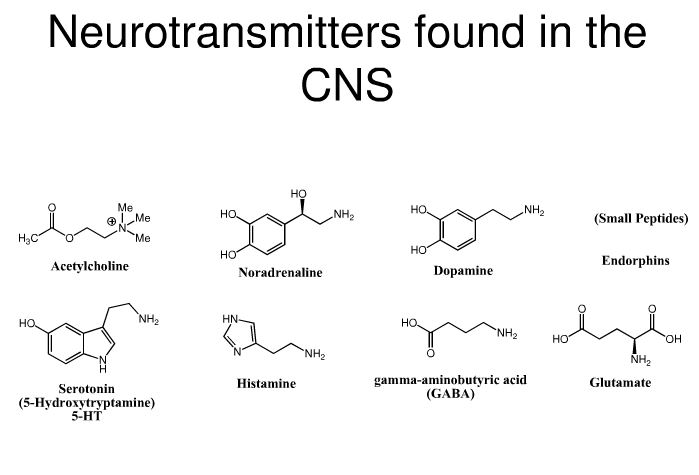

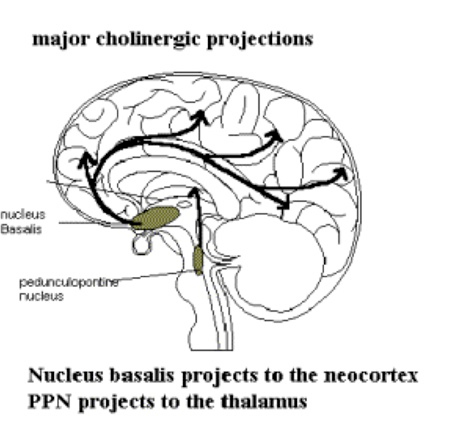

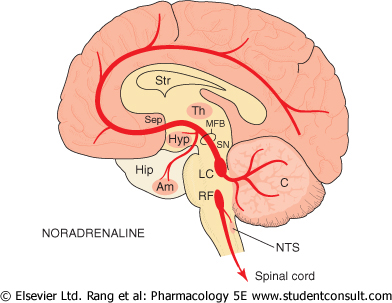

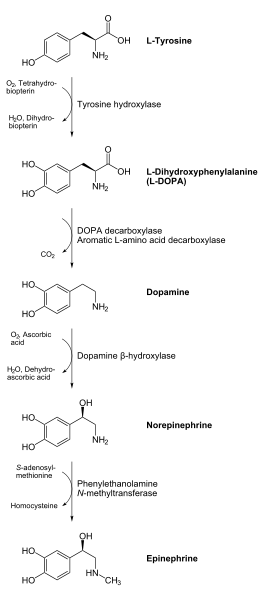

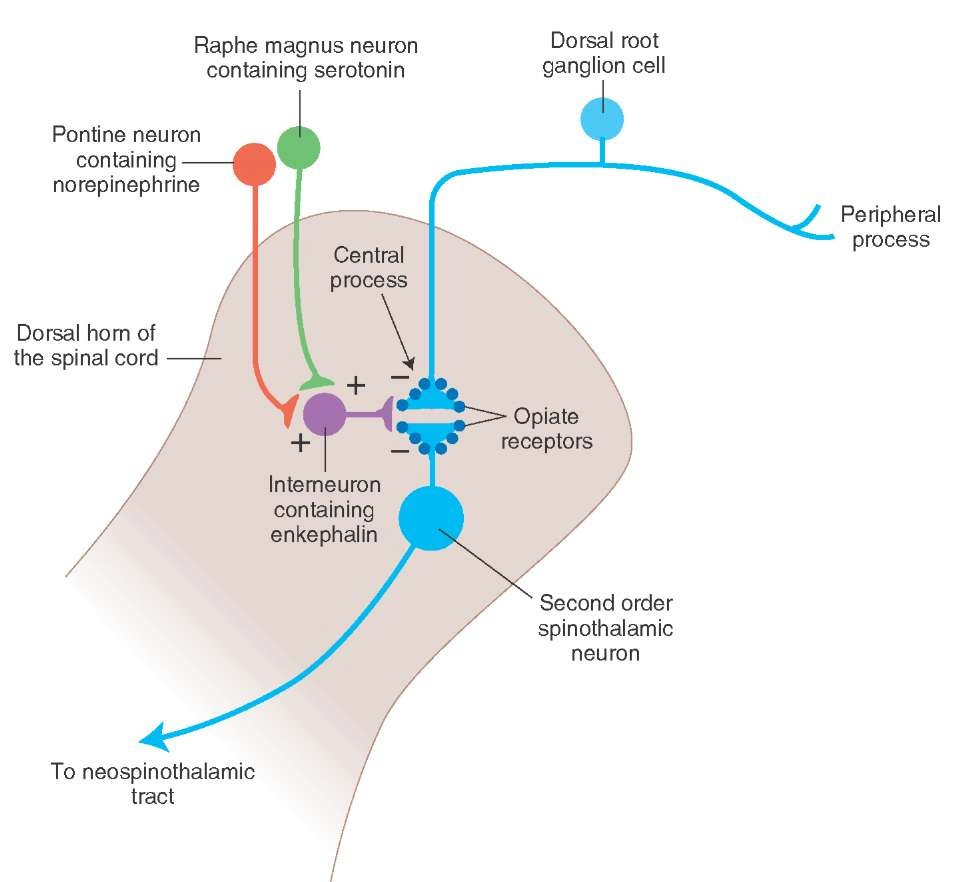

Modern histochemical techniques have shown that within the reticular formation there are groups of neurones with ill-defined boundaries that have characteristic chemical properties and neurotransmitters. Examples are the basal forebrain neurones that contain acetylcholine, and the raphe nuclei that contain serotonin. So there are subgroups of reticular neurones that contain specific neurotransmitters, and their axons have significant actions within the brainstem, forebrain and spinal cord.

The reticular formation neurones receive inputs from many different systems - somatosensory, proprioceptive, auditory, visual, etc. These neurones have non-specific inputs, not concerned with signalling the precision found in the main sensory pathways, but they mix and integrate the activity of many systems to produce an overview of all on-going activity in the sensory systems. Some reticular neurones are concerned with regulating the activity of the forebrain, as in sleep, arousal and waking (this is known as the Ascending Reticular Activating System, ARAS). Others, the 'Descending Reticular Formation' modulate the activity of spinal circuits, in the regulation of muscle tone, autonomic outflow or transmission of nociceptive information in the dorsal horn. |