|

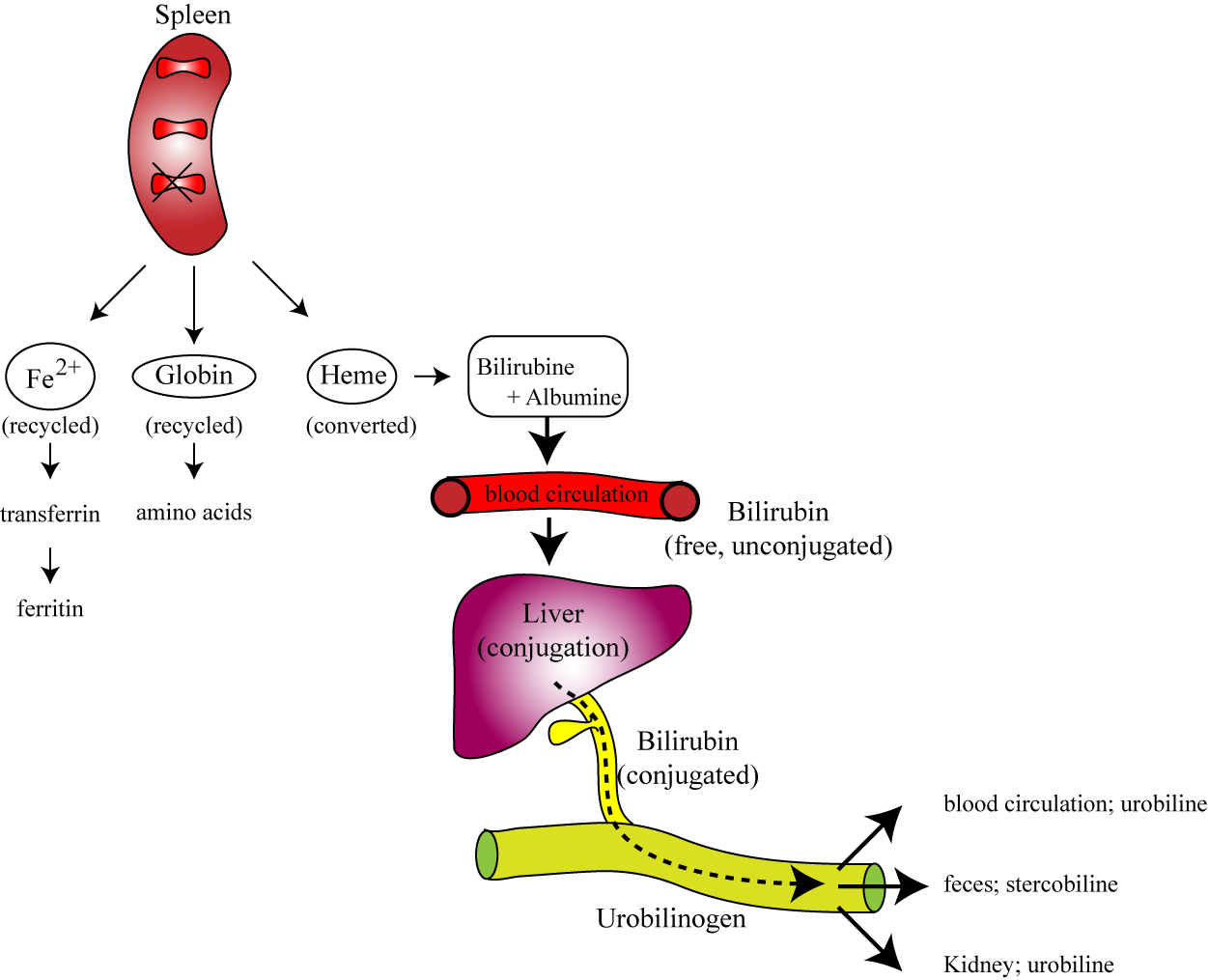

In the spleen, the components of the old destroyed RBC’s are recycled! |

Fe => Transferrin => Ferritin.

In other words, the iron is stored and saved. |

|

The globine is converted back into its amino acids which can be used for building other proteins. |

The heme is processed in a very special manner: |

|

The heme is converted, still in the spleen, first into biliverdin which is then converted into bilirubin. |

This bilirubin then appears in the blood and is bound to the blood transport protein: albumin. |

|

This bilirubin is called “free” or “indirect” bilirubin (depending on the book or the teacher or the country that you are being taught this). |

This free or indirect bilirubin is then transported by the blood to the liver |

|

This bilirubin is now called “conjugated” (!) or “direct” bilirubin. Whatever its name, this type of bilirubin is secreted into the bile. |

The bile flows into the intestine, where the bilirubin is converted, by the intestinal bacteria, into urobilinogen. |

|

This urobilinogen is absorbed by the blood and either goes back to the liver (to go back to the bile, to make a loop), or excreted by the kidney (as urobilin) or excreted via the stool (as stercobilin). |

Important; the stercobilin gives the stool its characteristic brown colour. If you don’t have stercobilin, then the stool becomes pale like clay. This is an important diagnostic tool to discover diseases of the gall bladder or the bile duct! |